Derby Loses The Monasteries

King Henry Vii died on died on 21 April 1509 at Richmond Palace in Surrey. His death was due to tuberculosis. Henry is buried in Westminster Abbey next to his wife, Elizabeth of York.

Young Henry VIII

When Henry VIII came to the throne in 1509 he was just shy of his 18th birthday. He was tall, robust, (apparently) handsome and athletic. As a young man, Henry VIII was considered to be the most handsome prince in Europe. He was tall, standing at six foot two which was taller than the average man of the time. He was broad of shoulder, with strong muscular arms and legs, and had striking red/gold hair. It is said that rather than looking like his father, he resembled his grandfather the late Edward IV. In the armoury of the Tower of London is a suit of armour that Henry wore in 1514. The king's measurements show that he had a waist of 35 inches and a chest of 42 inches, confirming that Henry was a well-proportioned, well-built young man.

In 1519, when Henry VIII was just twenty-eight years of age, the Venetian Ambassador Sebastian Giustinian visited the English court. He had the honour of seeing Henry VIII and recorded that he was "extremely handsome; nature could not have done more for him. He had a beard which looks like gold and a complexion as delicate and far as a woman's" He also stated that it was the "prettiest thing in the world to see the King playing tennis, his fair skin glowing through a shirt of the finest texture".

It is said that Henry was a passionate sportsman and had what seemed to be a never-ending flow of energy. He loved to be out-and-about and hated being bogged down by council meetings and paper work.

In 1509, Henry married his first wife, Catherine of Aragon. Catherine of Aragon had been the wife of Henry's older brother, Arthur, who had died aged 15. When Arthur died, Henry became first in line to the throne. Henry's father, Henry VII, died in 1509. A few months later, Henry was married and had been crowned King Henry VIII. Although Catherine was pregnant seven times during her marriage to Henry, only one baby survived past infancy – their daughter Mary. This was bad news for Henry, who wanted a male heir to carry on the Tudor line. Henry did not see his daughter as an heir at all.

Catherine of Aragon

Henry wanted to marry Anne Boleyn, and believed she could produce an heir, but he was still married to Catherine. When he discovered that Anne Boleyn was pregnant, Henry arranged to marry her in secret at Whitehall Palace - this marked the beginning of the break with Rome. King Henry VIII’s break with the Catholic Church is one of the most far-reaching events in English history. During the Reformation, the King replaced the Pope as the Head of the Church in England, causing a bitter divide between Catholics and Protestants. This loss of interest in Catherine was partly because Henry believed that his lack of heir was punishment from God for marrying his brother’s wife.

Henry VIII and Pope Clement VII

Henry had asked Pope Clement VII for his marriage to Catherine to be dissolved, but the Pope would not agree. Part of the reason that the Pope refused was because Charles V, the Holy Roman Emperor, had taken control of Rome - and Charles V was Catherine’s nephew.

Henry sought a way to terminate his marriage in a manner consistent with his Catholic faith. This was essential for political reasons, as a monarch going against Catholic doctrine risked disgrace and condemnation by the pope. Henry was also, by all accounts, a fairly devout Catholic. He was a known opponent of the Protestant Reformation that was taking shape on the continent, earning the title of Defender of the Faith from Pope Leo X for a treatise he wrote attacking Martin Luther.

Henry dispatched envoys to the pope in the hope of securing an annulment of his marriage, and even convinced Clement to establish an ecclesiastical court in England to rule on the matter. However, Clement had no intention of annulling the marriage. Apart from his doctrinal objections, he was more or less a captive of Charles V at the time and had no power to oppose Charles' insistence on keeping the marriage intact. Already enamoured with Anne Boleyn, who was known to have a strong interest in Luther and the Reformation, Henry had exhausted his options for remarriage within the church and decided that excommunication was a reasonable price to pay for independence from the pope and the possibility of fathering an heir.

Anne Boelyn

Henry removed Catherine from his court and married Anne (secretly in 1532, and publicly the following year). In doing so, he fundamentally altered the course of Christian and European history. After his remarriage, With the help of his wily advisor Thomas Cromwell, Henry issued a series of decrees that severed his kingdom from papal authority, ending the dominance of the Catholic Church and establishing the Church of England. Although the new church initially bore a strong resemblance to Roman Catholicism, these actions made Henry and his successors absolute rulers who did not answer to the pope, a rule which still survives with the current monarch today. England joined several German states, as well as Sweden, in rejecting Catholicism, setting the stage for centuries of religious, political, and military conflicts to come.

Henry VIII as head of the Church of England

Henry and Anne did have a child, but it was another girl. She would become Elizabeth I.

For most people in England, the storm erupted suddenly when, upon Henry VIII's request, Parliament abolished the Pope's authority and proclaimed the King as the "supreme head of the Church of England."

Henry VIII's break from the Roman Catholic Church and the declaration by Parliament that he was the supreme head of the Church of England marked the beginning of the English Reformation. During the Tudor era, it was absolutely crucial for a king to ensure a strong line of succession and the birth of a male heir to the throne. Although Henry VII had secured the throne after defeating Richard III in 1485, the fact that his ascent was achieved through violence had left his position somewhat precarious. Consequently, for his son, Henry VIII, the birth of a male heir was essential to maintain the continuity of Tudor rule and stabilize his power.

Even after the newly-established Church of England granted Henry VIII his annulment, Catherine of Aragon continued to remain loyal to her former spouse, partly to safeguard the interests of their daughter, the future Mary I. In her final letter to the now-remarried Henry, the dying Catherine wrote, "Lastly, I make this vow, that mine eyes desire you above all things. Farewell."

Following the news of Catherine's death in January 1536, Henry and his new queen, Anne Boleyn, made a public appearance dressed entirely in yellow attire. While some historians suggest that yellow might have been a mourning colour in the Spanish court of Catherine's birth, it appears more likely that the royal couple felt a sense of relief at Catherine's passing and appreciated the more cheerful connotations of the colour.

Henry VIII had a substantial ego. Prior to his reign, English kings were addressed as "Your Grace" or "Your Highness." However, after the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V was bestowed with the title "Majesty" in 1519, Henry VIII, in a bid not to be outdone, adopted the same term for himself.

King Henry VIII had a deep passion for jousting. When he was a young teenager, he was prohibited from participating in jousting competitions, as he was the sole heir to the throne. His father, Henry VII, feared for his son's safety, worrying that he might get injured or, worse, killed. However, when Henry ascended to the throne in 1509, he was remarkably athletic and enthusiastically embraced the excitement and chivalry of jousting.

During the early years of his reign, Henry VIII engaged in numerous spectacular jousting tournaments, one of which occurred on the 10th of March 1524. However, this particular joust did not unfold as planned for the King, and he faced a perilous situation that could have resulted in his demise.

In this jousting event, Charles Brandon, the Duke of Suffolk, was slated to joust against the King. Positioned at opposite ends of the tilt, the signal was given to commence, and both men urged their horses forward. Brandon, hindered by a helmet that offered limited visibility, and alarmingly, the King, who had forgotten to lower his visor, charged ahead. Onlookers cried out for Brandon to halt, but with his vision impaired and unable to hear, he continued forward and struck the inside of the King's helmet, causing splinters to explode over Henry VIII's face.

The Duke promptly disarmed himself and approached the King, demonstrating the restricted sight within his helmet and pledging never to joust against the King again. Had the King been even slightly injured, the King's attendants would have held the Duke accountable. Henry then summoned his armorers, who reassembled his equipment. He then took up a spear and executed six successful jousting courses, which reassured everyone present that he was unharmed. This brought great relief and comfort to all his subjects in attendance. Nevertheless, as a consequence of this incident, Henry suffered from migraines for the rest of his life.

Portrait of Charles Brandon, 1st Duke of Suffolk wearing the collar of the Order of the Garter.In 1525, Henry experienced another mishap during a vaulting exercise when the pole broke, causing him to fall into a water-filled ditch. His most severe injury occurred in 1536 when he fell from his horse during a joust, and the horse subsequently fell on top of him. Reports from the time suggest that Henry remained "without speaking" for two hours, which researchers interpreted as a sign of unconsciousness. This time, Henry was not as fortunate, and ulcers developed on both of his legs, causing excruciating pain. These ulcers never fully healed, leading to constant and severe infections. In February 1541, the French Ambassador recounted the King's dire condition.

“The King’s Life was really thought [to be] in danger, not from fever, but from the leg which often troubles him.”

The ambassador went on to point out how the king coped with this pain through excessive eating and drinking, which had a significant impact on his mood. Henry's increasing obesity and persistent infections continued to raise concerns within Parliament.

The jousting incident, which had deprived him of his beloved pastime, also restricted Henry from engaging in physical exercise. His final suit of armour in 1544, just three years before his death, indicated that he weighed a minimum of three hundred pounds, with his waist expanding from a slim thirty-two inches to a hefty fifty-two inches. By 1546, Henry had grown so large that he relied on wooden chairs for mobility and hoists to lift him. He needed assistance to mount his horse, and his leg continued to deteriorate. It's this image of an excessively obese king that most people recall when asked about Henry VIII.

The unending pain undeniably played a significant role in Henry's transformation into a bad-tempered, unpredictable, and irritable monarch. Persistent chronic pain can severely impact one's quality of life (even in modern times), and without the benefits of contemporary medicine, Henry must have endured excruciating daily suffering, which undoubtedly affected his disposition. Henry's later years were a far cry from the valiant and charismatic prince he was in 1509.

Many began to notice and make private of assessments of, Henry becoming paranoid, irrational, unpredictable, ill-tempered, and even dangerous.

Henry VIII's suit of armour

Henry proved to be lacking in military prowess. Despite his limited talents in warfare, England found itself embroiled in perpetual conflicts during his reign, yielding little to show for it in the end. His repeated endeavors to conquer Scotland led to the formation of an alliance between Scotland and France against England. Additionally, his association with the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V soured during Henry's attempts to annul his marriage to Catherine of Aragon, who happened to be the emperor's aunt.

In 1542, Henry and Charles V once again united their forces to wage war against France, England's long-standing rival, marking the third French war of Henry's reign. At this juncture, Henry's obesity had advanced to the point where he could no longer lead his troops on horseback, necessitating his transport on a litter along the battle lines. Even after Charles signed a treaty with the French, Henry persisted in the campaign, depleting his treasury in the process. Ultimately, all he had to show for the war was the relatively insignificant port of Boulogne, which would soon return to French control.

Despite inheriting a substantial fortune, equivalent to around £375 million in today's currency, Henry's extravagant spending habits and the cost of his opulent court, which was among the most lavish in history, imposed a constant strain on his finances. His costly continental wars further eroded his resources. His inheritance diminished rapidly, and although annual revenues from rents and dues paid by his subjects remained consistent, inflation and rising prices took their toll. On two occasions during his reign (in 1526 and 1539), Henry devalued England's currency, providing temporary relief but ultimately exacerbating inflation.

Dale Abbey, Derbyshire

Over the following decade, Henry's power and wealth increased significantly. Every English monastery was closed, their possessions confiscated and redirected to Henry's coffers. Those who opposed this transformation, including his former confidant and counsellor Thomas More, were subjected to execution under stringent treason statutes.

The dissolution of the monasteries, also referred to as the suppression of the monasteries, encompassed a sequence of administrative and legal procedures that unfolded between 1536 and 1541. These procedures culminated in Henry VIII's dismantling of monasteries, priories, convents, and friaries in England, Wales, and Ireland. Their revenues were seized, their assets liquidated, and arrangements were made for their former members and functions.

Although the initial intention of this policy was to enhance the Crown's income, a substantial portion of the former monastic properties was sold to finance Henry's military campaigns in the 1540s. Henry received the authorisation to carry out these actions in England and Wales through the Act of Supremacy enacted by Parliament in 1534, which designated him as the Supreme Head of the Church in England, thus severing ties with papal authority. The First Suppression Act of 1535 and the Second Suppression Act of 1539 further expedited this process.

While Thomas Cromwell, the Vicar-general and Vice-gerent of England, is frequently associated with leading the Dissolutions, his primary role was overseeing the project. Initially, he had aspired to utilise it for the reform of monasteries rather than their closure or asset seizure. The Dissolution project was initiated by England's Lord Chancellor Thomas Audley and Richard Rich, who headed the Court of Augmentations.

Thomas Cromwell

(It was almost certainly to celebrate his appointment as

Master of the Jewels that Thomas Cromwell commissioned Hans Holbein,

the most celebrated artist of the age, to paint his portrait in around 1532-33.)

The reaction of Derby to this news remains uncertain. There was no apparent upheaval. However, the change came closer to home in 1536 when Thomas Cromwell, who served as Henry's Chancellor, dispatched agents to Prior Thomas Gainsborough. Prior Gainsborough "surrendered" the Priory and Hospital of St. James to these agents. The Hospital of St. Leonard (the Lazar House) and King's Mead Nunnery also faced dissolution. These smaller establishments had dwindled to the point where only a handful of residents remained, and their poverty meant that the agents gained little from them.

The fate of the larger monasteries swiftly followed. In 1539, Cromwell sent Dr. John London to the Friary. Dr. London convinced the Prior, Friar Lawrence Sponar, to sign a deed of surrender, likely through promises of a pension or the use of threats. As soon as this was accomplished, Thomas Thacker arrived to seize the Friary's valuables and plate for the Royal Treasury. The Friary was subsequently transformed into a private residence owned by John Sharpe, a "gentleman."

On October 24th, 1538, Cromwell's commissioner, Dr. Legh, along with a businessman, Sir William Cavendish, arrived at Darley Abbey. The Abbot had anticipated the adverse turn of events and had already sold the right to appoint a priest to St. Peter's Church to Peter Marten of Stapleford. The Abbot ultimately acquiesced, but the two agents seemed to have mishandled or manipulated the accounts, leading to their reprimand. The monks who were evicted from these institutions received pensions commensurate with their rank. In the Derby area, the assessment of these pensions was overseen by Sir William Cavendish and Sir John Porte.

In a mere three years, Derby lost its priories, hospitals, nunnery, and abbey. Friars and monks disappeared from its streets. The valuable possessions were sent to the King's Treasury, and the structures were left unroofed, with the lead even melted down. As a result, today, we lack noble ruins for visitors to explore and for the locals to take pride in.

Sir William Cavendish

Sir William Cavendish was an English politician, knight and courtier. Cavendish held public office and accumulated a considerable fortune, and became one of Thomas Cromwell's "visitors of the monasteries" during the dissolution of the monasteries. He was MP for Thirsk in 1547. In 1547 he also married Bess of Hardwick, and the couple began the construction of Chatsworth House in Derbyshire which started in the year 1552 and still stands today.

Chatsworth House

(I highly recommend the book Stags and Serpents: The Story of the House of Cavendish and the Dukes of Devonshire. Written by John Pearson)

Thomas Cromwell possessed exceptional abilities and an immense capacity for hard work. For a decade, he wielded immense influence over England's political and religious landscape. He ruthlessly eliminated those who opposed him and his royal master, most notably his rival Thomas More and Henry's infamous second wife, Anne Boleyn.

Cromwell served as a brutal enforcer to the tyrannical King Henry VIII, characterised by his unscrupulous, ambitious, ruthless, and corrupt political nature. He cared little for the policies he implemented, as long as they enriched him personally.

It's accurate to say that a significant portion of Cromwell's responsibilities involved orchestrating executions and undermining others to maintain his position at court. Anne Boleyn had been expecting a child at the time of her marriage to Henry, but she gave birth to a girl (the future Elizabeth I) rather than the desired son. Several miscarriages followed, with the last occurring in January 1536. This appears to have prompted Henry to instruct Cromwell to find a way out of the marriage. What Cromwell did was morally reprehensible. He conspired to have Anne executed based on rumours and hearsay stemming from Anne's flirtatious conduct. Cromwell fabricated a case of adultery against her, implicating no fewer than five men, including her own brother George. Anne was arrested on May 2, 1536, and taken to the Tower of London, where she was tried and subsequently found guilty just over two weeks later. Cromwell was among the witnesses who gathered to witness her execution on May 19.

This marked the pinnacle of Cromwell's career. Not only had he removed a woman who had become a dangerous adversary to the King and himself, but he swiftly aligned his family with the new queen, Jane Seymour, to whom Henry was betrothed the day after Anne's execution.

A photochrom from 1890, showing The Tower of London, where Anne Boleyn was kept prisoner before being executed.

Numerous accounts of the execution of Queen Anne Boleyn exist, each shaped by personal biases, nationalities, and the intended audience of the narrators.

In Alison Weir's meticulous work, "The Lady in the Tower," which delves into the downfall of Anne Boleyn, the author meticulously presents the diverse reported versions of Anne's final moments. While some reports, including those from those not allowed in like Chapuys, suggested that no foreigners witnessed the spectacle, it appears that at least four individuals—Frenchman Lancelot de Carle, an anonymous Spaniard, a Portuguese subject, and an "Imperialist"—managed to gain access to the Tower of London or knew someone who did. Many English citizens, from tower workers to crown agents to ordinary people, also gathered at the Tower on that late spring morning to witness Anne's execution.

Initially, accounts diverged regarding the location of the execution, though historians today concur that it likely occurred on the expansive green area, now a gravelled parade ground between the White Tower and the Waterloo Block. Weir's account describes Anne being led to the scaffold, adorned in either a grey or black "night robe" with a red under-skirt and a white ermine cape, accompanied by "four young ladies" whose names went unrecorded by those present. While the Imperialist source claimed she seemed "feeble and stupefied" as she ascended the scaffold, most agreed with the Englishman Crispin, Lord Milherve, who noted that "when she was brought to the place of her execution her looks were cheerful."

All witnesses agreed that Anne requested a moment to address the crowd. She began to speak, with her most critical detractor being an anonymous writer of the Spanish Chronicle, a narrative about Henry VIII, possibly authored by a servant to the Spanish ambassador or a Spanish merchant. This Chronicle author hinted at having sneaked in the night before to watch the execution or having a close friend who did. According to this source, Anne, given a final opportunity to admit her guilt, "would not confess, but showed a devilish spirit and was as if she were not going to die." The Chronicle author claimed that Anne's speech included the words, "everything they have accused me of is false, and the principal reason I am to die is Jane Seymour, as I was the cause of the ill that befell my mistress." At the mention of Jane Seymour, the King's new mistress and future wife, the Chronicle reports that Anne was silenced by the men on the scaffold. She looked around as if seeking a reprieve and obstinately denied her guilt.

In all the eyewitness accounts, except for one, Anne adamantly refused to admit guilt for adultery or treason. Only in the Imperialist account did Anne "raise her eyes to heaven" and "beg God and the king to forgive her offences."

While the Spanish and Imperialist accounts naturally displayed bias against Anne, the French accounts were inclined to favour her. Anne had spent her formative years in France, in the entourage of Henry's sister Mary, who had married the French King. She spoke French fluently, dressed in the French fashion, and was often considered more culturally French than English.

Lancelot de Carle, the secretary to the French ambassador, was so moved by Anne's trial and execution that he composed a poem, "A Letter Containing the Criminal Charges Laid Against Queen Anne Boleyn of England," dated June 2, 1536. In the poem, he described how Anne "went to the place of execution with an untroubled countenance. Her face and complexion never were so beautiful. She gracefully addressed the people from the scaffold with a voice somewhat overcome by weakness, but which gathered strength as she went on." As she implored those present to show compassion for those who had condemned her, "spectators could not refrain from tears."

The most widely accepted version of Anne's final speech was recorded by Edward Hall, a member of Parliament and a city official of London, who authored the "Chronicle of England":

"Good Christian people, I am come hither to die, according to law, for by the law, I am judged to die, and therefore I will speak nothing against it. I come here only to die, and thus to yield myself humbly to the will of the King, my lord. And if in my life, I did ever offend the King's Grace, surely with my death I do now atone. I come here to accuse no man, nor to speak anything of what whereof I am accused, as I know full well that aught I say in my defence doth not appertain to you. I pray and beseech you all, good friends, to pray for the life of the King, my sovereign lord and yours, who is one of the best princes on the face of the earth, who has always treated me so well that better could not be, wherefore I submit to death with good will, humbly asking pardon of all the world. If any person will meddle with my cause, I require them to judge the best. Thus I take leave of the world, and of you, and I heartily desire you all to pray for me. Oh Lord, have mercy on me! To God I commend my soul!"

This version, which combines a politically correct praise of the King with a bold refusal to admit guilt, is echoed in several eyewitness accounts, including those of the unknown Portuguese subject and the Englishman Anthony Anthony, the surveyor of the Tower's ordnance. The wording varies among versions, but the core message remains consistent. It is the basis for the speech Anne delivered, though historians like Eric Ives offer a slightly simplified rendition. In this version, Anne began, "I have not come here to preach a sermon; I have come here to die."

Another observer, possibly the Lord of Miherve, attested that she added, "be not sorry to see me die thus, but pardon me from your hearts that I have not expressed to all about me that mildness that became me." The Portuguese subject astonishingly claimed to have heard her murmur, "Alas, poor head. In a very brief space, thou will roll in the dust on the scaffold, and as in life you did not merit the crown of a queen, so in death you deserve no better doom than this."

In her final moments, Anne knelt down, ready to receive the executioner's blow. To one chronicler, "she appeared dazed," while "fastening her clothes about her feet." To another, she displayed strength and serenity as she "prepared to receive the stroke of death with resolution, so sedately as to cover her feet with her nether garments." Even the simple act of whether her eyes were covered remains a point of contention. According to Weir:

The Spanish Chronicle insists that Anne refused to have her eyes bandaged, and that her gaze disturbed the executioner. However, three other witnesses state that one of her ladies, weeping, "came forward to do the last office" and blindfolded her with a "linen cloth." Ales, whose landlord related the details, says that Anne herself "covered her eyes."

Anne began to pray loudly, beseeching God to receive her soul. Soon, it was over, her head cleanly severed by the executioner's single stroke. As her maids carried away her body, several witnesses to her death dispersed from the green, some heading to their desks to record their observations, while others recounted the event to friends interested in the historical record.

Jane Seymour

It didn't take long for tensions to surface in Cromwell and Henry's relationship. Cromwell orchestrated a marriage between Jane Seymour's sister Elizabeth and his son Gregory, effectively cementing himself as part of the royal family.

Discontent against the Reformation reached a boiling point with the Pilgrimage of Grace in October 1536. The rebels left no doubt that their primary target was the "heretic Cromwell," not the King. Henry's trust in Cromwell wavered, and he began to distance himself from his chief minister. In a notorious incident in 1538, he resorted to violence against his once-favoured advisor. One courtier recounted how Cromwell was "roughly handled, receiving blows to the head and being shaken like a dog."

By 1539, Cromwell was desperate to regain favour and believed he had found the perfect solution. Jane Seymour had passed away after giving birth to the long-awaited son, Edward, in 1537. The quest for a fourth wife for Henry commenced promptly, and Cromwell identified a new bride for his monarch. Cromwell's choice was Anne of Cleves, a German princess who promised to bring a valuable new alliance to England. Before agreeing to the idea of this new marriage, Henry had Holbein paint Anne's portrait. Henry was so captivated by Anne's portrait that marriage negotiations were set in motion immediately, and Anne arrived in England in December 1539. However, when Henry met her in person, he was thoroughly disappointed. He exclaimed, "I like her not! I like her not!" to the beleaguered Cromwell, complaining that Anne was "far from the way she had been described." The marriage was annulled a few months later.

Hans Holbein the Younger's portrait of Jane Seymour

Contrary to common belief, the Anne of Cleves marriage debacle did not mark the end for Cromwell. Despite the gleeful observation from a contemporary that "Cromwell is tottering," the King quickly forgave him. In April 1540, Henry elevated him to the rank of Earl of Essex. This move incensed Cromwell's adversaries, notably the Duke of Norfolk, who were determined to rid themselves of this low-born upstart once and for all. They initiated a whispering campaign against Cromwell, alleging that he was scheming to rebel against the King.

It took very little to stoke the suspicions of the aging and paranoid King, who wasted no time in ordering Cromwell's arrest on charges of treason and heresy. On June 10, 1540, Cromwell was conveyed to the Tower of London. Given his stature as the country's preeminent lawyer, his enemies did not dare risk putting him on trial. Instead, they convinced the King to present a bill of attainder before Parliament.

The bill was passed in late June, and Cromwell was condemned to death. His sole chance for clemency rested on persuading Henry to pardon him. Consequently, he penned a series of impassioned letters from the Tower. His final missive concluded with a desperate postscript: "Most gracious prince, I cry for mercy, mercy, mercy."

However, the King remained unyielding, and on July 28, 1540, Cromwell was executed. It took three blows of the axe from the "ragged and butcherly" executioner to sever his head.

Following the display of his head on London Bridge, it was eventually reunited with the rest of his remains and interred at the Tower's Chapel Royal of St. Peter ad Vincula, alongside his former rivals Anne Boleyn and Thomas More.

Thomas Cromwell had been one of the most exceptional royal servants in history, masterminding extensive reforms across all facets of England's religious, political, and social life. He was a man of genuine religious conviction, responsible for translating the Bible into English to provide all of Henry's subjects with access to God's word. He personally crafted numerous statutes that revolutionised government and administration, significantly augmenting the power of Parliament.

According to Charles de Marillac, the French ambassador, who wrote to the Duke of Montmorency in March 1541, Henry VIII later regretted Cromwell's execution. The King attributed it to his Privy Council, contending that, "on the pretext of several trivial faults he [Cromwell] had committed, they had made several false accusations which had resulted in him killing the most faithful servant he had ever had."

Catherine Howard

Catherine's uncle, the Duke of Norfolk, secured a place for her at Court in the household of the King's fourth wife, Anne of Cleves. As a young and attractive lady-in-waiting, Catherine quickly garnered the attention of several men, including the King and Thomas Culpeper. During the initial stages of her tenure at court, prior to Anne of Cleves' arrival, the connection between the King and Catherine received little notice. It appears that he found her appealing, and whenever their paths crossed, they openly engaged in flirtation, but little else seemed to occur.

However, as Anne arrived and the King's interest waned, an opportunity began to unfold for Catherine. Before this point, Catherine and Thomas Culpeper had entered into a quasi-relationship that was not yet sexual. Although later testimonies suggest that Culpeper expected it to progress in that direction, he also professed his love for Catherine, which was likely more driven by lust than genuine affection. Catherine rejected his advances, prompting him to turn his attention to another woman within the Queen's household. This deeply affected Catherine, who seemed to have some emotional attachment to him during this period. On one occasion, she broke down in tears in front of her fellow maids of honour. Before this, she had been the one controlling the duration and termination of her relationships.

Word of the rumoured impending marriage between Catherine and Culpeper reached Francis Dereham, who returned to court to confront them. Catherine chastised him once more, and he returned to the dowager duchess's household, which he had previously sought to leave, as Catherine was no longer there. Believing this desperation to be temporary and expecting it to subside, Agnes Howard denied his request.

Although the King had displayed little interest in Anne from the outset, Thomas Cromwell failed to find a new match for him, presenting an opportunity for Norfolk. The Howards sought to regain the influence they had enjoyed during Anne Boleyn's reign as queen consort. According to Nicholas Sander, a religiously conservative figure, the Howard family may have viewed Catherine as a symbolic leader in their efforts to restore Roman Catholicism in England.

As the King's attraction to Catherine intensified, so did the influence of the House of Norfolk. Her youth, beauty, and vivacity captivated the middle-aged monarch, who claimed he had never met anyone like her. Within months of her arrival at court, Henry bestowed upon Catherine gifts of land and opulent fabrics. He affectionately called her his 'very jewel of womanhood.' (The phrase that he referred to her as his 'rose without a thorn' is likely a misconception.) Charles de Marillac, the French ambassador, described her as "delightful." Holbein's portrait depicted a young auburn-haired woman with the characteristic hooked Howard nose, and Catherine was said to have a "gentle, earnest face."

On 28 July 1540, King Henry and Catherine were married by Bishop Bonner of London at Oatlands Palace. Catherine was a teenager, and Henry was 49. She adopted the French motto "Non autre volonté que la sienne," meaning "No other will but his." The marriage was publicly announced on 8 August, and prayers were offered in the Chapel Royal at Hampton Court Palace.

Great Gate, Royal at Hampton Court Palace

Catherine's involvement with Henry's favorite male courtier, Thomas Culpeper, during her marriage to the King is a matter of contention. According to Dereham's later testimony, Culpeper had replaced him in the Queen's affections. Catherine had considered marrying Culpeper during her time as a maid-of-honor to Anne of Cleves.

In a love letter, Culpeper affectionately referred to Catherine as "my little, sweet fool." It has been suggested that in the spring of 1541, Catherine and Culpeper were meeting secretly. Allegedly, their clandestine rendezvous were arranged by one of Catherine's older ladies-in-waiting, Jane Boleyn, Viscountess Rochford (Lady Rochford), who was the widow of Catherine's executed cousin, George Boleyn, Anne Boleyn's brother.

There were individuals who claimed to have witnessed Catherine's previous sexual behavior while she lived at Lambeth, and they reportedly approached her for favors in exchange for their silence. Some of these individuals may have been appointed to her royal household. John Lassels, a supporter of Cromwell, approached the Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Cranmer, informing him that his sister Mary refused to become part of Queen Catherine's household, citing that she had observed Catherine's "loose" conduct during their time together at Lambeth. Cranmer then questioned Mary Lassels, who alleged that Catherine had engaged in sexual relations while under the Duchess of Norfolk's care, prior to her relationship with the King.

Upon receiving this information, Cranmer initiated actions to discredit his rivals, the Roman Catholic Norfolk family. Lady Rochford was interrogated, and, fearing torture, she agreed to cooperate. She revealed how she had watched for Catherine while Culpeper made his exits from the Queen's chambers.

During the investigation, a love letter penned in the Queen's distinct handwriting was discovered in Culpeper's chambers. This is the only surviving letter attributed to her, apart from her later "confession."

On All Saints' Day, 1 November 1541, the King, while praying in the Chapel Royal, received a letter detailing the allegations against Catherine. On 7 November 1541, Archbishop Cranmer led a delegation of councillors to Winchester Palace in Southwark to interrogate her. Even the resolute Cranmer found Catherine's distraught and incoherent state deeply pitiable, remarking, "I found her in such lamentation and heaviness as I never saw no creature, so that it would have pitied any man's heart to have looked upon her." He ordered the guards to remove any objects she could potentially use for self-harm.

Establishing the existence of a pre-contract between Catherine and Dereham would have invalidated her marriage to Henry. However, it would have allowed Henry to annul their marriage and banish her from court to a life of poverty and disgrace instead of executing her, although there is no indication that Henry would have chosen this alternative. Catherine steadfastly denied any pre-contract, asserting that Dereham had raped her.

Catherine was stripped of her title as queen on 23 November 1541 and incarcerated in the new Syon Abbey, Middlesex, formerly a convent, where she remained throughout the winter of 1541. She was compelled by a Privy Councillor to return the ring that had belonged to Anne of Cleves and had been given to her by the King. This symbolised the revocation of her regal and lawful rights, and she would not see the King again. Despite these actions, her marriage to Henry was never officially annulled.

Both Culpeper and Dereham were charged with high treason and arraigned at Guildhall on 1 December 1541. They were executed at Tyburn on 10 December 1541, with Culpeper being beheaded and Dereham being hanged, drawn, and quartered. In accordance with custom, their heads were displayed on spikes on London Bridge. Many of Catherine's relatives were also imprisoned in the Tower, tried, found guilty of concealing treason, and sentenced to lifelong imprisonment and forfeiture of their possessions. Catherine's uncle, the Duke of Norfolk, distanced himself from the scandal by retreating to Kenninghall and composing a letter of apology, laying the blame on his niece and stepmother.

Culpeper and Dereham were arraigned at Guildhall on 1 December 1541 for high treason. They were executed at Tyburn on 10 December 1541, with Culpeper being beheaded and Dereham being hanged, drawn, and quartered. In accordance with custom, their heads were displayed on spikes on London Bridge. Many of Catherine's relatives were also imprisoned in the Tower, tried, found guilty of concealing treason, and sentenced to lifelong imprisonment and the forfeiture of their possessions. Her uncle, the Duke of Norfolk, distanced himself from the scandal by retreating to Kenninghall, where he penned a letter of apology, shifting all blame onto his niece and stepmother.

This course of action retroactively resolved the issue of Catherine's alleged pre-contract and definitively deemed her guilty. No formal trial took place.

On the eve of her execution, Catherine purportedly spent several hours practicing how to position her head on the execution block, which had been provided upon her request. While she faced her execution with relative composure, she appeared pale and frightened, requiring assistance to ascend the scaffold. Although popular folklore suggests that her last words were, "I die a Queen, but I would rather have died the wife of Culpeper," there is no eyewitness account supporting this claim. Instead, reports indicated that she adhered to the traditional final words, seeking forgiveness for her sins and acknowledging that she deserved to die "a thousand deaths" for betraying the king, who had treated her with great kindness. She expressed that her punishment was "worthy and just" and requested mercy for her family and prayers for her soul. This was in keeping with the speeches delivered by individuals executed during that era, likely aimed at protecting their families, as their final words would be relayed to the King. Catherine was subsequently beheaded with the executioner's axe.

Catherine Parr

Leveraging her late mother's connection with Henry's first queen, Catherine of Aragon, the widowed Catherine Parr seized the opportunity to rekindle her friendship with the former queen's daughter, Lady Mary. By the 16th of February in 1543, Catherine had firmly established herself as a member of Mary's household. It was during this time that Catherine came to the King's attention.

Although she had initiated a romantic relationship with Sir Thomas Seymour, the brother of the late queen Jane Seymour, Catherine considered it her duty to accept Henry's proposal over Seymour's. In an effort to distance Seymour from the royal court, he was given a post in Brussels. (Given how rumours spread about Henry's ex-wives, this would have been a very safe option.)

Catherine and Henry VIII were joined in matrimony on the 12th of July in 1543 at Hampton Court Palace. She became the first Queen of England to also hold the title of Queen of Ireland following Henry's adoption of the title "King of Ireland." Interestingly, Catherine marked the third wife of Henry to bear the name Catherine. Their union was cemented by shared royal and noble ancestors, as they were distant cousins through multiple connections. They were third cousins once removed through Ralph Neville, 1st Earl of Westmorland, and Lady Joan Beaufort (a granddaughter of Edward III) by way of Henry's mother and Catherine's father. Through their fathers, they were double fourth cousins once removed, sharing Thomas Holland, 2nd Earl of Kent (son of Joan of Kent) and Lady Alice FitzAlan (a granddaughter of Henry, 3rd Earl of Lancaster), along with John of Gaunt, 1st Duke of Lancaster (son of Edward III) and Katherine Swynford.

Upon ascending to the role of queen, Catherine appointed her former stepdaughter, Margaret Neville, as her lady-in-waiting. She also extended positions within her household to her cousin Maud, Lady Lane, and her stepson John's wife, Lucy Somerset. Catherine played a crucial role in reconciling Henry with his daughters from his first two marriages and developed a positive relationship with Henry's son, Edward. Her uncle, Lord Parr of Horton, became her Lord Chamberlain when she became queen.

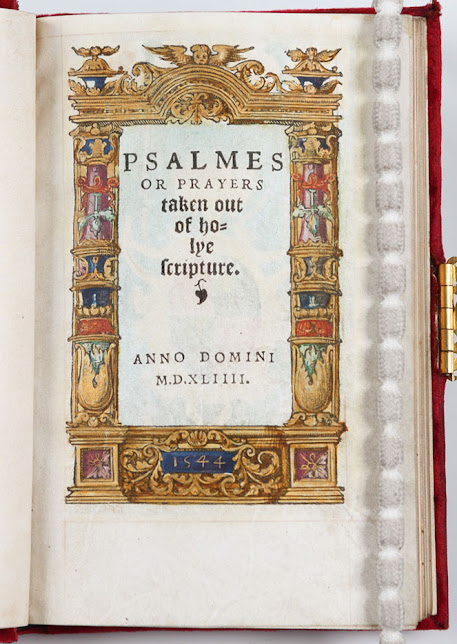

Catherine Parr's work, "Parr's Psalms or Prayers taken out of Holy Scriptures," was printed by the king's printer on the 25th of April in 1544. It was an anonymous translation of a Latin text by Bishop John Fisher from around 1525, which had been reprinted on the 18th of April in 1544. Fisher had been executed in 1535 for refusing to take the oath of supremacy, and his name did not appear on the title page of the book. Catherine's volume served as a piece of powerful wartime propaganda, designed to aid Henry in the war against France and Scotland by invoking prayers from his people.

In a relatively brief span of time, Derby was associated with six queens who were married to the king. It is estimated that during his 36-year rule over England, Henry executed as many as 57,000 individuals. The people of Derby were well aware that no one was safe, not even Henry's closest friends or inner circle, or even his wives. This explains the scarcity of critical accounts of Henry VIII. Nevertheless, it is not to say that such discussions did not occur privately. One well-known instance of it happening publicly was during Henry VIII's Great Matter when Friar Peto served Catherine of Aragon and Princess Mary as a confessor. On Easter Sunday in 1531, he angered King Henry VIII by delivering a sermon that likened the king to Ahab and Anne Boleyn to Jezebel. He cautioned the king to act to avoid Ahab's tragic fate and to avoid the dogs licking up his blood, much as they did with Ahab.

In his later years, Henry experienced a considerable increase in weight, with a waist measurement of 54 inches (140 cm), and required mechanical aids to move around. He suffered from painful, pus-filled boils and possibly gout. His obesity and other medical issues could be traced back to a jousting accident in 1536, which led to a leg wound. This accident aggravated a previous injury he had sustained, making it difficult for his doctors to treat. The chronic wound festered and became ulcerated, limiting his physical activity compared to his previous levels of vitality.

The theory that Henry had syphilis has been largely dismissed by historians. Some have suggested that his wives' frequent pregnancies and his mental deterioration could be indicative of him being Kell positive and having McLeod syndrome.

According to another theory, Henry's history and physical condition may have been a result of traumatic brain injury following his jousting accident in 1536, leading to a neuroendocrine cause of his obesity. This analysis posits that growth hormone deficiency (GHD) was the reason behind his increased adiposity and contributed to significant behavioural changes observed in his later years, including his multiple marriages.

On his deathbed at Whitehall Palace, Henry uttered his last recorded words. When asked which priest should attend him, the King replied, "I will first take a little sleep, and then, as I feel myself, I will advise upon the matter."

The following morning, Henry had lost the ability to speak. He passed away in the early hours of 28 January 1547 at the age of 55. The next day, Prince Edward and Princess Elizabeth were informed of their father's death. The children, aged 9 and 16, clung to each other, weeping and apprehensive about their future.

Henry VIII's body was conveyed to Windsor Castle in a solemn funeral procession and laid to rest beside Jane Seymour in St George's Chapel.

Following his death, Henry's body was placed in a lead coffin, which burst open during transport, causing his bodily fluids to drip onto the floor of Syon Abbey. When plumbers arrived for repairs the next morning, a dog entered with them and was witnessed licking up the fluids.

Despite the profound religious and social upheaval of the Reformation, it is noteworthy that Henry VIII remained conservative in his beliefs and died as a Catholic. In 1521, he authored a book condemning the arch-reformist Protestant Martin Luther, earning him the title 'Defender of the Faith' from the Pope. This title is still used by the British sovereign today.

Edward VI

When the boy king, Edward VI, sat on his father's throne, his Protestant advisers dissolved both chantries and guilds. The chantries at St. Peter's, St. Werburgh's and All Saints' in Derby were closed. The Bridge Chapel was shut up and its hermit dismissed. The guilds vanished. Last of all, the College of All Saints' was dissolved, its priests turned out, its splendid furniture taken away and its estates sold to Thomas Smith and Aaron Newsam for £346. Amongst other land they acquired farms in Little Chester, as well as a meadow in the Wardwick (not a built-up area then) which All Saints' had owned for five hundred years.

Edward VI abolished Mass and ordered services to be said in English instead of Latin. Archbishop Cranmer's English Prayer Book and an English translation of the Bible appeared in Derby churches.

Scarcely had Robert Liversage departed from this world when the act of offering prayers for the deceased became prohibited by law. Consequently, his last will was disregarded, and the intended chantry in St. Peter's never came to fruition. His chaplain, Robert Lay, was forbidden from supplicating for his soul or that of his wife, Alice. The funds he had designated for these purposes have since been a cherished charitable asset for the town.

Ancient chair in St Peters, Derby

Edward VI entered the world as a robust infant. His father, Henry, expressed immense delight in his son. In May 1538, there were eyewitness accounts of Henry joyfully cradling Edward in his arms and presenting him to the public from a window, bringing great comfort to the people.

By September of the same year, Lord Chancellor Lord Audley reported Edward's rapid growth and vitality, while other descriptions portrayed him as a tall and cheerful child. Recent historians have challenged the traditional notion that Edward VI was a sickly boy. Although he faced a life-threatening "quartan fever" at the age of four, and despite occasional illnesses and poor eyesight, he generally enjoyed good health until the final six months of his life.

Initially, Edward was entrusted to the care of Margaret Bryan, the "lady mistress" of the prince's household. She was later succeeded by Blanche Herbert, Lady Troy. Up to the age of six, Edward grew up, as he later noted in his Chronicle, "among the women." His formal royal household, initially overseen by Sir William Sidney and later by Sir Richard Page, the stepfather of his aunt Anne (the wife of Edward Seymour), adhered to Henry's strict standards of security and cleanliness. Henry emphasised that Edward was "this whole realm's most precious jewel." Visitors described the prince as a contented child, lavishly supplied with toys, comforts, and even his own group of minstrels.

Edward VI's coronation took place at Westminster Abbey on Sunday, 20 February. To ensure the young king's comfort, the ceremonies were shortened, given his tender age and the inappropriateness of some rites due to the Reformation.

During Edward's reign, the nation faced economic difficulties and social unrest, leading to riots and rebellion in 1549. An expensive conflict with Scotland, initially successful, concluded with military withdrawal from both Scotland and Boulogne-sur-Mer in exchange for peace. Edward took a keen interest in religious matters, overseeing the transformation of the Church of England into a recognisably Protestant institution. His father, Henry VIII, had severed ties with the Roman Church but largely maintained Catholic doctrine and rituals. Under Edward, Protestantism was officially established in England, leading to reforms that included the abolition of clerical celibacy, the Mass, and the introduction of mandatory services in English.

In 1553, at the age of 15, Edward fell seriously ill. When it became clear that his illness was terminal, he and his council devised a "Succession Plan" to prevent a return to Catholicism in the country. Edward designated his Protestant first cousin once removed, Lady Jane Grey, as his heir, excluding his half-sisters, Mary and Elizabeth. This decision led to a dispute after Edward's death, and Jane was deposed by Mary just nine days after becoming queen.

Queen Mary I, also known as Mary Tudor, was infamously referred to as "Bloody Mary" by her Protestant opponents. Devoutly Catholic, she sought to reinstate Catholicism in England through predominantly persuasive means. However, her regime's harsh persecution of Protestant dissidents resulted in the execution of hundreds for heresy. This led to her earning the epithet "Bloody Mary." During the Marian persecutions, Mary ordered the burning at the stake of over 280 religious dissenters in just five years.

During the short reign of Queen Mary, a Catholic, there was a return to the customs of the old Church. Mass was again celebrated in Latin and the English Prayer Book put aside. The outburst of religious persecution led to a scene in Derby unequalled in its pity and terror. Joan Waste, the blind daughter of a baker, had grown accustomed to having the New Testament read to her. Some of her neighbours accused her of disavowing Roman Church doctrines, leading to her trial by Dr. Ralph Barnes, the Bishop of Lichfield. The Church found her guilty, but as it lacked the authority to carry out executions, Joan was handed over to the two Bailiffs, Richard Ward and William Bembridge, for her sentence - to be burnt to death.

The stake was firmly planted in Windmill Pit, located off Burton Road. On August 1st, 1556, with everything in readiness, the twenty-two-year-old blind Joan, accompanied by her brother, made the journey from All Saints' Church to Windmill Pit. There, she was bound to the stake and, invoking Christ's mercy, was suspended over the fire with a rope. When the rope eventually burned through, she descended into the flames. Waste was expected to endure eternal suffering for her beliefs.

Windmill Hill Pit in the 19th Century (It was known as the "ordeal pit" in the eleventh century)

Waste was born blind in 1534, with her twin brother Roger, to a Derby barber, William Waste and his wife, Joan. By the age of twelve she had learned to knit as well as how to make ropes (her father was also a ropemaker).

Queen Mary made no attempt to restore religious houses to Derby. She granted pensions to the priests driven away from All Saints'. Some of its property she handed to the Corporation, the burgesses agreeing to pay two priests to serve in church and find houses for them.

What happened to Derby School, when All Saints' College was dissolved, we do not know. Probably it went on somehow. Queen Mary, however, restored it by charter to the Corporation when it was known as the "Free School." A new schoolhouse was built in St. Peter's churchyard.

The effects of these changes, given below, were far-reaching:

(I) The loss of the stately priories and their churches deprived the town of its finer public buildings, of the activity that centred round them and of the trade and employment they created.

(II) Once the monasteries had fed the poor; who did that now?(III) The Abbeys had lodged and attracted distinguished guests, but of such we hear far less during the next hundred years.(IV) In Henry VIl's reign there were over eighty clerics, or one to every thirty of the population; in Edward Vi's five, or one to every six hundred people.(V) Church festivals were fewer and less picturesque; the guilds had gone and nothing replaced them. How was this gap in people's lives filled?

The town lost its proud position as Church headquarters for a wide area. The whole way of life changed, and seems poorer, less attractive and beset with problems such as unemployment and increase in the poor. Yet there was no upset, not a murmur from the townsfolk, or none that has come down to us. They took it all meekly enough, even looking upon the awful fate of Joan Waste without a protest.

Because of an incident in which a certain Griffiths tried to kidnap George Curzon of Kedleston, then a minor, in St. Peter's Church, we first hear of an old custom. The town bell rang and the people, rushing to St. Peter's, foiled Griffiths's attempt. Whenever something important happened, the town bell called the people together.

An ancient inventory tells us what Markeaton Hall in Derby was like in Henry VIII's time. Let us go with Robert Liversage, the rich dyer, on a visit to the Mundys. He had his horse saddled and rode along lrongate out of the town to Markeaton and along the drive to the house.

Markeaton Hall

After being welcomed at the door by Sir John Mundy himself, Liversage stepped straight into the hall, the chief room of the old house which went up to the roof. Here was the high table, a massive oak trestle with an old cloth on it. Beside it were forms for people to sit on. This table was not much used, for it belonged to days, already gone, when the Lord of the Manor, his guests and retainers dined together in the hall. By the window was a "framed table," that is, one made by a joiner, which drink was served, bought recently off Mr. Francis Pole of Radbourne. There was no carpet on the floor which might have been strewn with rushes.

The rooms were not built along passages, so when Liversage went round the house, he would go straight from one room into another. These rooms, called chambers, we should say were "bed-sitting-rooms." Even the parlour had a great four-poster bed as well as a trussing-bed, or one which could be folded up and taken on a journey. Mundy, you see, did not trust the beds which he might find in the Inns. In the parlour, too, were a wooden cradle and a cupboard, called an ambry. The chimney with its iron gate was a novelty and had been recently built on to the outside of the wall.

Besides the parlour there were six other bedrooms, or chambers, each with a four-poster bed, covered with a canopy, or tester, and hung round with curtains. Mundy's own bed had a "coarse" mattress with a feather-bed on top, a bolster, woollen blankets and tapestry coverlet, but no sheets are mentioned. It was hung round with red and green serge curtains, so that when closed for the night the great bed was like a room within a room. It needed to be. Such old houses were draughty and unheated and people then wore no nightclothes. There was also a trundle-bed, that is, a small bed on wheels, normally pushed under the great bed, and useful when the house was full of guests often the case, for the Mundy’s liked to entertain. Unusual was the "turned" chair, that is, one with round legs turned on a "pole-lathe." Pictures had not yet become the fashion, and there were only two in the house a painted "panel" of St. Dorothy, and Sir John's own arms. Only the cook had a private chamber. Women servants slept in one room in the house; men servants in a loft over an out-building.

Besides the hall there were two other "reception" rooms. One was the great chamber "where we dine," as Sir John said. Here he proudly showed Liversage the dining-table of "fir" and the carved-oak chest newly brought from London. There were also a trestle table and a sideboard, but no chairs. The other room Sir John called his study, although he had only six books. Four of these were manuscripts written by monks, and among them was the Iliad. He had two printed books, including Henry VIII's Primer just published.

A primer (in this sense usually pronounced /ˈprɪmər/, sometimes /ˈpraɪmər/) is a first textbook for teaching of reading, such as an alphabet book or basal reader. The word also is used more broadly to refer to any book that presents the most basic elements of any subject.

Three Primers Put Forth in the Reign of Henry VIII: Viz, A Goodly Prymer, 1535,

The Manual of Prayers or the Prymer in English, 1539,

King Henry's Primer, 1545

Near the window was his writing table with inkstand and a sandbox. Sand was scattered over writing to dry ink before blotting-paper was invented. In a red chest bound with iron he kept his papers, tenants' leases, wills, deeds and other documents. Nearby was a pair of scales with troy weights, because in those days, when coins were easily clipped, money was always weighed. There was no arm-chair for the squire, not even an ordinary chair, but only a form with a cushion, upon which Sir John and Liversage sat down to chat.

Like other manor-houses Markeaton Hall had its private chapel. Two sets of vestments, one of cloth of gold and the other of red velvet, together with the altar cloth, remained after the Reformation. Sir John had a Latin psalter written on parchment and bound with a silver clasp.

If Sir John showed Liversage behind the scenes, he would have found the "offices" spacious. The buttery, or pantry, near the hall held the bread-bin, the pewter tankards, the leathern wine bottles, ale barrels, candlesticks and a mustard mill to grind mustard seed. From the buttery they would go into the kitchen, where shining brass pots hung round the wall. There were several spits, one of which had a goose on it and was being turned by a kitchen boy before a great wood fire, over which saucepans hung on pot-hooks from a chimney bar. There were pewter plates on a shelf, frying-pans, gridirons, kitchen knives and a stone mortar for making pastes.

In the yard were the brew-house with its vats, and the bakehouse with kneading tub and table. Bread was baked in a round stone oven, after a wood fire kindled within had heated it up. Beyond were the stables, in which Liversage's horse was resting, and byres for cattle. Swine and poultry were kept. So were peacocks, not only to strut on the lawn, but to grace the table at special feasts. Oats and barley were stored in barns with the simple farm-gear. Fishing nets, nets for catching partridges, Sir John's plate armour, bows, arrows and pikes could be found in an attic.

They dined in the great chamber. We should notice that there were no forks or table-knives. Meat was received upon a square piece of bread, called a trencher, which soaked up the gravy. Before table-forks were used hashes and pastes eaten with spoons were popular. Almonds, figs and raisins were bought in Derby, whilst honey was used for sweetening, unless Sir John had at a great price obtained a little sugar in London. They washed the meat down with ale out of pewter tankards. Liversage's horse would be brought to the door before the moon set, for to ride in the dark along miry lanes was dangerous. If you wish to know what kind of a house Liversage himself might have lived in, The Dolphin in Queen Street, built in 1530, will give you an idea.

John Mundy was born in High Wycombe, Buckinghamshire, the son of Sir John Mundy and Isabel Ripes. In 1515 Mundy served as a Sheriff of London. In 1522 he became Lord Mayor of London. He was knighted by King Henry VIII in 1529 (some say 1523). In 1516 he purchased from Lord Audley the manors of Markeaton, Mackworth and Allestree, all now part of the city of Derby. He built a Tudor House and his descendants replaced the old manor house with a new mansion in about 1750 Markeaton Hall.

.jpg)

01%20(1).jpg)

.jpg)